Another area of my research focuses on language politics in classrooms and educational institutions more generally, from the K-college level. With an emphasis on English, writing, and literacy education, this area draws on K-12 qualitative education scholarship, studies of race in literacy classrooms at the college classrooms by composition-rhetoric scholars, and texts in critical pedagogy and critical race theory.

While my work primarily falls within composition-rhetoric—which tends to focus mostly on college-level contexts—K-12 education research offers key ideas and methods around Literacy and race that are applicable, though in varied ways, at different school levels. As college instructors, we of course teach former K-12 students and thus comprehending dynamics around race and writing in the full spectrum of schooling contexts is key to understanding students at any level. Significant research on rhetorics of racial othering and white supremacy in educational contexts comes from K-12 scholarship. For instance, Gloria Ladson-Billings notes that commonplace discourses around the “achievement gap” frame BIPOC and multiply minoritized students as in some way Lacking compared to an assumed white norm. Bolstered by neoliberal logics of race-evasive (Annama et al.) meritocracy, “deficit” rhetorics blame differences in “achievement” on the actions of individual students, suggesting these problems could be cursorily fixed rather than interrogating the Larger systems of oppression that foreground schooling (Patel; Leonardo). Eve Tuck relatedly notes that “damage”-centered ideologies that underlie much education research on minoritized communities can end up “pathologizing” and overemphasizing “oppression [as] singularly defin[ing]” them.

Given this, scholars forwarding pedagogies of decolonial and/or racial justice suggest that as educators we must first and foremost be “answerable”—as Patel puts it—to the communities we teach by combatting, head-on, schooling’s colonial and supremacist Legacies and continuing violence. Drawing on this research, the texts in H. Sami Alim and Django Paris’ edited collection propose “culturally sustaining pedagogies” as a praxis that center the Lived experiences—and, relatedly and most saliently for me, Literacy practices—of students, rather than automatically privileging a normative white, cis gender, heterosexual, middle-class student, or “white Listening subject” (Flores & Rosa). Expanding upon Ladson-Billings’ classic “culturally relevant pedagogy,” Alim, Paris, and other scholars including April Baker-Bell, Jonathan Rosa, and Nelson Flores suggest that we need to move beyond mere “relevance” for students to creating educational settings that work with communities to actively dismantle and decolonize the white-washed, linguistically (and ultimately, materially) violent modes of engaging with Literacy in many classrooms.

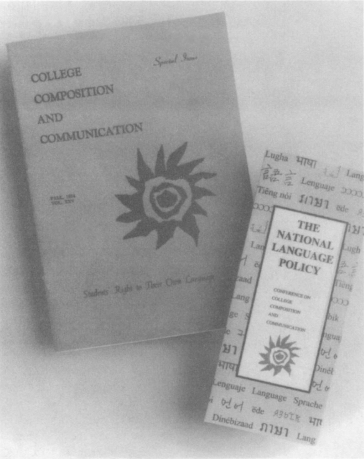

Though many of the ideas discussed above come out of K-12 research contexts outside literacy/writing classrooms, some Composition-Rhetoric scholars have been asking similar questions about possibilities for antiracist, social-justice oriented approaches to teaching writing for decades. Back in 1974, the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) statement “Students Rights to Their Own Language” (SRTOL) demanded that writing students be able to draw on “their own patterns and varieties of language—the dialects of their nurture or whatever dialects in which they find their own identity and style.” As composition historiographers note, it’s crucial to highlight that in large part this document only came to be written and subsequently published thanks to the instance and tenacity of CCCC’s Black Caucus at the time.

We need to ask ourselves whether the rejection of students who do not adopt the dialect most familiar to us is based on any real merit in our dialect or whether we are actually rejecting the students themselves, rejecting them because of their racial, social, and cultural origins.

Students’ Right to their Own Language (1974)

Now nearly fifty years later, SRTOL has been canonized in our field and is widely embraced as a significant theoretical landmark, yet its key concerns remain unaddressed in practice in many writing classrooms and programs. Indeed, as Paul Kei Matsuda notes, the myth of the composition classroom in particular as a Western-dominated, monolingual space remains quite strong–even in universities that are racially and linguistically heterogeneous. For compositionists and English educators, then, supporting the voices of all students within the context of the university remains an ongoing challenge. However, as Baker-Bell et. al, Elaine Richardson, and Carmen Kynard note, contemporary contexts such as the Movement for Black Lives might serve as an opening to interrogate anti-blackness and white supremacist violence that exists in the world and in English/writing classrooms, and to radically reorient the ways we think about English education–and education more generally–given this.